Teaching PL

by Matthias Felleisen

15 Apr 2020

Changed in version 1.2: Sun Apr 26 18:00:19 EDT 2020,

Robby spotted my Scribble problems; Eli, Jason, Stephen, and Shriram noticed some more glitches and typos

Changed in version 1.1: Sat Apr 25 19:14:56 EDT 2020,

Shriram, Ben Greenman, Vincent St-Amour, Matthew, and Arjun pushed

back, questioned my write-up, reinforced some points, and also pointed

out typos. So this is a major rewrite.

Changed in version 1.0: Thu Apr 16 11:10:29 EDT 2020,

first release

This spring semester I taught the undergraduate programming language

course—

They may only think they wish to become developers. We still owe them a chance. Since 2002, I have continued to develop an undergraduate core curriculum that focuses on systematic software design. My take is that 99% of our undergraduate students wish to become software developer, and it is our job to prepare them as well as possible.

1 Why Do We Teach PL

Some instructors want to show students what their favorite language can do for them. Others wish to expose their class to ideas that are of exciting to them. Some hold a near-religious belief about the landscape of programming languages and how people must view it. If you belong to one of these groups, this note is not for you.

PPL is primarily an introduction to the fundamental principles of the PL landscape that every developer must understand.

PPL should once again reinforce the lessons of our developer-oriented curriculum.

The researchers in programming languages—

the oldest area in computer science— have developed the deepest understanding of the development of programs. This understanding deeply informs the design of our curriculum. The assignments in this course will reinforce these lessons and demonstrate their usefulness.

2 Transfer

When I started teaching PPL with EOPL at Rice in 1987, it was obvious to me that students would easily be able to apply what I taught them. Like everyone else, I had anecdotes.

In 1988, I had a vocal a senior who expressed his doubts about the

usefulness of the material in class. A short time after graduating, I bumped into him— |

I didn’t use the word “transfer” back then. We all

have such anecdotes. But, we train hundreds of students and we don’t

hear from more than a few. Also we all have great teaching

evaluations."Buy him women,

give him beer.

Do everything,

to keep him here"

an evaluation from one of my first years at Rice Those don’t cut it either. Our

enthusiasm for PL is infectious, our ideas are exciting. But do the

students learn something? Can they translate it somehow, somewhere

later into ideas of their own? Or does it all just stay a cool memory

about a professor with an exhilarating classroom presence?

In the mid 1990s, I started to have doubts about transfer, triggered by observations in my PPL course.

What problem did you observe? | In ’94 we started teaching the early version of the design recipe in earnest. |

And? | In ’95 and ’96 I noticed that students in PL didn’t remember it. |

If they programmed in the same language ... | Yes? |

I’d call this “retention.” | Sure. But they didn’t. |

Did they not program in Scheme in both courses? | No. I had this bee in my bonnet that I let them start with whatever language. |

And? | I’d show them solutions in C++, Java and Racket, and they’d switch to Racket voluntarily. |

Did this happen? | Absolutely. |

Why? | Because they could not apply the design recipe to create interpreters in their languages. |

How did this make you feel? | Great, because I was stupid. |

Stupid? | Sure, I thought they’d see the light and program in Racket ever after. |

Wouldn’t you call it “arrogant”? | Yes. But that doesn’t make it better. I soon realized that these students would have to program in some other language. Racket just wasn’t going to dominate the world. |

When did this happen? | By the time I started at Northeastern, it had become crystal clear. And it was also clear that here students thought I was a magician and Racket was a magic wand. |

How come? | Some students told me so. They couldn’t imagine using the same tricks outside of class and especially not in other languages. |

My actual response was to teach the design recipe in the undergraduate core curriculum in three different languages and settings. And that’s half the reason I hadn’t taught PPL in 18 years.

A couple of years ago I also had some conversations with Shriram on

students’ understanding of aliasing. He observed that his incoming PPL

students did not have a firm grasp of the idea, regardless of

syntax. Over the course of PPL, they improved their

understanding—

3 My Approach

let students work in their “favorite” language

use Racket in lectures as my “second favorite” language

dispense with parsing as a “model view control” problem

work exclusively with abstract syntax (structs, not S-expressions)

deliver lecture code in a functional style but occasionally give direct reminders on how this would work in an object-oriented language

have the students present and explain their solutions in class.

A large number of students chose Java, the language of our second and third course. An equally large number opted for Python. Otherwise there were a handful of (Typed) Racket pairs, and one each of Haskell, Rust, and TypeScript. One pair started in OCaml but switched to Typed Racket after one assignment.

The concrete input syntax was JSON, though I mostly used nested arrays. To drive home the idea of abstract syntax, one homework assignment had the students parse two different concrete syntaxes into the same abstract syntax: JSON and S-expressions. I pointed them to a web repository with S-expression parsers for every one of the chosen languages.

I posed another homework problem (HW8) that explicitly addressed “transfer.” It asked the students to write a “transpiler” from JSON to programs in their chosen language. They had to measure for how many of around 100 tests their interpreter and their transpiled programs produced the same outputs.

I specifically worked on aliasing with three different homework

assignment that forced them to work through the idea at all levels:

test programs, their own programming language, and the

environment-store distinction. The good students clearly grokked

it—

4 Student Response

I wanted to explore several aspects with Piazza polls once the pandemic hit but in the end I left it at three. As in ordinary elections, only about half the students voted though Piazza says that almost all of them looked at the posts.

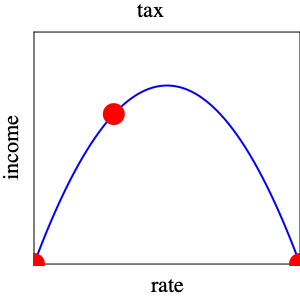

The first question that interested me concerned the choice of programming

language. As you can tell from figure 21 students supported

this option with an overwhelming majority. But, to my surprise, a fair

number voted for an option that I added as a teaser—

Due to network problems, one of my teaching assistants turned a lecture in mid April into a conversation. She asked students whether they would use the same programming language again. All Java and Python programmers who responded said they would not use these languages again. Not everybody responded to her question, though.

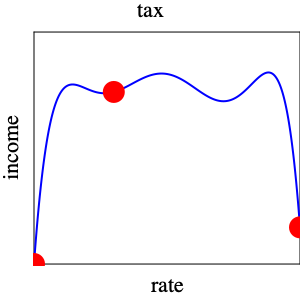

The second question was about the input language. Frankly, I had hoped that the exercise on S-expressions had convinced them of the simplicity of S-expressions over JSON. Well, figure 22 tells you that they love what they (think they) know.

Figure 22: What kind of input language should the course use?

For the third question, I allowed students to check multiple options. The goal was to find out whether explicitly talking about transfer and explicitly assigning a “transfer homework” had helped. I think figure 23 leaves no doubt about how students feel.

“Feel” I used the word “feel” here because I am perfectly aware that a Piazza poll is not scientific evidence. It does provide us with an impression of how students perceive the course and possibly suggests that explicitly addressing their hearts and minds helps them learn. And that may help us teach.

5 Postscript: Call/CC

I could not stomach asking my teaching assistants to grade cps-ed Java programs. So instead I pursued the following path.

First, I asked the students to implement a cps transpiler for our model language. I really like the way I taught cps-ing this year.

Second, for the last few weeks I switched from interpreters to C, CC,

CEK, and CESK machines. I wanted to figure out how that went over but

due to the pandemic they worked through just two homework assignments

with abstract machines. And I could not figure out how to ask them to

compare the approaches.—

Acknowledgments Conversations with Shriram on his PL course reinforced my desire to try this approach. “Coffees” with my current PhD students plus Jason Hemann and Ben Lerner served as a sounding board during the entire fall 2019 semester. Their comments helped me shape several elements; Michael Ballantyne’s encouragement to switch to abstract machines at the end helped me make the move that I had imagined ever since I wrote the Redex book with Matthew and Robby.

Teaching such a course requires an outstanding team of assistants. I was blessed to work with Leif Andersen, Suzanne Becker, Julia Belyakova, and Dustin Jamner.